“The Returned Yank is the meanest form of animal that ever came amongst us…there is no greater menace to this country.” - Seán Flanagan, Fianna Fáil politician (February 1952 parliamentary debate)

“He's a nice, quiet, peace-loving man, come home to Ireland to forget his troubles. He's a millionaire, you know, like all the Yanks.” - The Quiet Man (dir. John Ford, 1952)

The Returned Yank is, in the simplest terms, the Irish American who comes “home”: sometimes to visit, sometimes to stay, often with money, opinions, or both. In Irish life and popular culture, this figure has been met with everything from celebration to (more often than not) derision, suspicion, and satire. Recent portrayals continue to reflect this ambivalence: in season 15 of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, the Gang’s chaotic trip to Ireland devolves into a grotesque send-up of diaspora fantasies. Mac’s (Rob McElhenney) desperate search for his Irish roots results in him spiraling over the revelation that he may not be Irish at all, while Charlie (Charlie Day) uncovers a surprising connection to his “gibberish” speaking (Gaeilgeoir) pen pal. The show may lean into absurdity, but beneath the humor lies a sharp critique of how ideas of heritage can quickly venture into obsessive and hollow territory. The episodes reflect a broader discomfort with return migration as both a sentimental myth and a site of cultural friction, where authenticity is questioned and belonging is anything but guaranteed.

Whether it knew what it was doing or not, Always Sunny was playing into a storied trope of Irish Americans returning to Ireland, one most famously explored in John Ford’s popular film The Quiet Man. Aside from being mobilized as a literary device and use as an arbiter in one of the most important debates in post-Independence era Ireland––whether it should remain a "traditional" society or seek to modernize––it is important to emphasize that the Returned Yank was more than a symbol upon which to project the issues the Irish faced in the twentieth (and now twenty first) century. It represented the stories of real life members of the Irish diaspora, be they migrants returning to Ireland after years abroad or many generations removed, that made a tangible impact on the means by which the Irish fashioned their cultural identities and expressions.

In tracing (across several parts) the imperial and economic forces that shaped and contested the figure of the Returned Yank, this series will consider how return migration left a lasting imprint on Irish and Irish American cultural life. That imprint endures not only in film, television, and tourism, but in the contemporary resentments between Irish-born and Irish diaspora communities. Today, the Returned Yank remains a lightning rod for anxieties around authenticity, class, and cultural ownership that have often spilled into online spaces where diaspora-bashing and “homeland”-gatekeeping continue to thrive.

So – how did we get here? To understand how the Returned Yank became such a charged symbolic and social figure, we’ll need to look beyond the realm of film and folklore and into the geopolitical and economic forces that shaped postwar Ireland and its relationship with the United States.

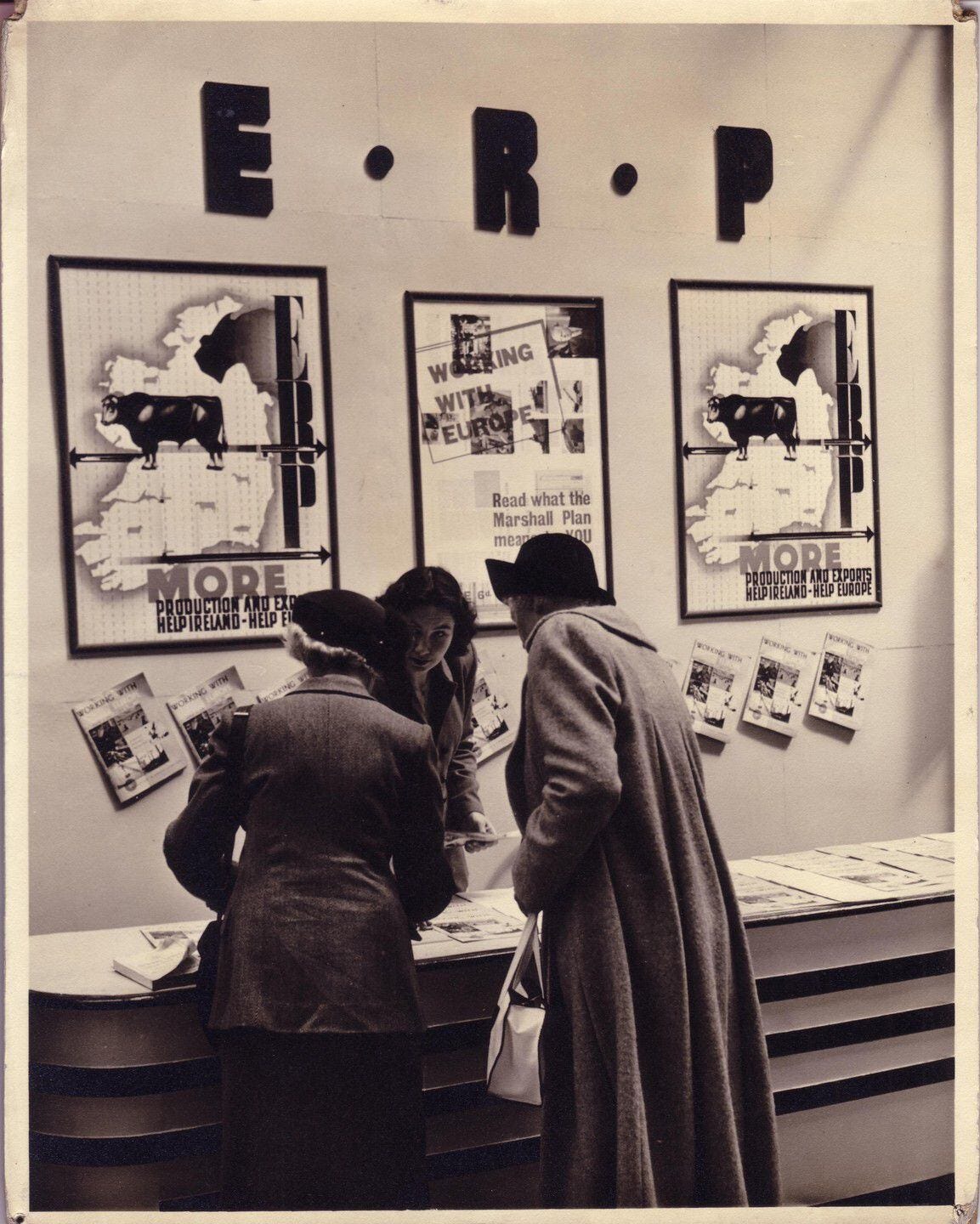

Several American aid programs were established in the immediate aftermath of the war, but ultimately proved small-scale and relatively piecemeal. When U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall officially announced the European Recovery Program in the wake of World War II, the idea and process existed in outline only; yet the scaffolding the ERP (hereinafter referred to as the Marshall Plan) put forth in 1947 would eventually set in motion the construction of the largest, and first complete, administrative structure that sought to fulfill both American and European goals heading into the postwar period.1

The origins of the Marshall Plan laid in the steadfast conviction of the American government that its values and framework were not only superior, but that it held a moral obligation to see to the permanent installation of these same basic tenets in other countries. Rising fears of domestic economic recession, emerging Cold War threats, and the return to prominence of the State Department’s role in foreign policymaking likewise ensured the Marshall Plan’s popularity within the American political conversation. The Plan effectively sought to remake the Old World in the likeness of the New, and operated as far more than an instrument of US foreign policy; it sought to stabilize the European economy, boost production, and “modernize” Western Europe by encouraging capitalistic, consumerist societies that would simultaneously thwart the expansion of communism.2

The 1948 arrival in Dublin of the ECA (Economic Cooperation Administration), set up by the United States to manage the Plan’s administration, heralded the inauguration of the Marshall Plan in Ireland. Over the next four years, Ireland would receive $147 million in funding from the United States through the program––$128 million (roughly $1.5 billion today) of which was comprised of interest-bearing loans.3

The ECA quickly asserted that America’s priorities lay in encouraging the growth of Ireland’s mixed-farming, food-exporting economy and in developing industry as a secondary activity for the time being. Irish agriculture was to be turned into an efficient, modern sector of the economy; a sector where the ECA’s guiding principles––unity, growth, productivity, and modernization––would be realized.4 By 1949, however, the allocation of funds had shifted beyond recognition to a nearly wholly industrialization-minded approach. With immense pressure placed on the Irish to develop “longer-term,” more “valuable” means by which to bolster the economy, ECA chief Joseph Carrigan increasingly emphasized three areas that the US determined held the most potential for the growth of Ireland’s (and the US’s, by extension) capital: building a tourism industry, developing more lucrative dollar exports, and mineral exploration.5

The response to this shift in economic strategy was a largely frustrated one. Minister for Industry and Commerce Daniel Morrissey was a vocal opponent, as were several prominent trade unionists and leftist contingents apprehensive of the consequences of mass production in the wake of Ireland’s industrial disputes just a few decades before.6 The hospitality industry, too, felt it had “very little to learn" from the American example.”7 The advice proffered by the ERP in light of this shift––emphases on efficiency and productivity, market diversification, export promotion, attracting foreign investment––rested rather universally uneasily with a government and people who were by and large committed to a more introspective, self-sufficient, rural vision for Ireland.8

Continued receipt of Marshall Plan funding was made contingent upon Ireland bolstering its tourist infrastructure, although this was never explicitly stated.9 It was precisely this issue that was being debated when Flanagan embarked on the diatribe that opens this article in which he labels Irish American visitors as “menace[s].”10 For Flanagan, the “yanks” that Marshall Plan initiatives brought in were “too demanding in their pursuit of high-quality amenities and service” and instead ought to focus on “appreciate[ing] the evidences of antiquity here…the character of the Irish people, the beauty of the wild country of Connemara, of a certain stretch of my own native county and of Donegal…the beauty of every county in this glorious country of ours.”11 As if to anticipate Flanagan’s remarks, first-generation Irish American journalist John McNulty wrote about his two-month stay in Ireland for The New Yorker in 1949, claiming that what kept him there so long was that “they [the Irish] do the things we used to do but don’t do any more…children recite poetry, people take long walks, sit by the fire, talk without a radio going.” It is into this post-war economy––one of an American incentivized tourism industry within Ireland that emphasized a foundationally consumer based relationship between visitor and culture––that many parts of the Irish diaspora found themselves re-engaging with the country of their “mythic” origins.

This same reputed pre-modernity of Ireland is what draws protagonist Sean Thornton back to his birthplace in The Quiet Man; his fatal knockout of an opponent in the boxing ring represents a turning point for Irish American disillusionment with cosmopolitanism. Thornton longs to escape the “steel and pig iron furnaces so hot it makes a man forget his fear of hell,” and, given the opportunity to return, opts to settle instead within the pastoral realm of digestible nostalgia.12 Thus, as historian Luke Gibbons argues, “the romantic appeal of the Irish countryside and the search for home is offset against the disenchantment of life in the metropolis…traumas from the past for which modernity has no answer.”13 The figure of the Returned Yank, in its exemplification of real and imagined “modern” American influence on Ireland’s pastorality, then solidified itself as the sandbox of emotions within which Irish Americans and Irish people were, and are, forced to reckon with their sense of self and culture.14

Stay tuned in the coming weeks for The Myth and Measure of the Returned Yank, Part 2: The Irish Folklore Commission.

Whelan, Bernadette. “Ireland and the Marshall Plan.” Irish Economic and Social History 19 (1992): 56.

Whelan, Bernadette. “Adopting the ‘American Way’: Ireland and the Marshall Plan, 1947-57.” History Ireland 16, no. 3 (2008): 30–33.

Brown, William Adams, Jr. and Opie, Redvers. American Foreign Assistance. Washington, The Brookings Institution (1953): 237.

“Copy of report by ECA chief to US special representative in Paris,” 15 November 1948. Record Group 286, File 846.3, Mission Review Ireland 1949/50 Programme, 15 December 1949 National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

Whelan, Bernadette. “The New World and the Old: American Marshall. Planners in Ireland, 1947-57,” Irish Studies in International Affairs 12 (2001): 186.

Groutel, A. “Ireland and the Marshall Plan: E.C.A.’s Maneuvering to Promote Dollar Tourism.” Irish Economic and Social History 49, no. 1 (2022): 124.; Bulletin of the Irish Section (in English), Mar 1948. Box: 44, Folder: 15 (Material Type: Mixed Materials), Microfilm Reel Number 57. Servies V, Part A, TAM.103 Max Schachter Papers, Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

Conversation with Morrissey, Cosgrave and McCarthy, signed Harry Clement, 21 April 1950 RG. 469, entry 1251, Taft III, Technical Assistance, Box 1. Records of Foreign Assistance Agencies 1942-1963, National Archives and Records Administration.

See footnote 1.

Zuelow, Eric G.E. Making Ireland Irish: Tourism and National Identity since the Irish Civil War (Syracuse University Press, 2009): 19.

Ibid. 53.

Houses of the Oireachtas, “Dáil Éireann Debate - Thursday, 28 Feb 1952,” text, February 28, 1952, Ireland, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1952-02-28.

Moynihan, Sinéad. “‘Quiet Men’: Film and Filmmaking in Returned Yank Fictions of the Troubles,” in Ireland, Migration and Return Migration: The “Returned Yank" in the Cultural Imagination, 1952 to Present (Liverpool University Press, 2019): 43-46.

Gibbons, Luke. The Quiet Man (Cork University Press, 2002): 38.

Cleary, Joe. “Introduction: Ireland and Modernity,” in The Cambridge Companion to Modern Irish Culture, ed. Joe Cleary and Claire Connolly (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005): 1.

Excited for Part 2!